2. The NHS will reduce pressure on emergency hospital services

1.21. Boosting ‘out-of-hospital’ care in the way set out above makes sense in its own right. But there are also very substantial pressures across the NHS in looking after emergency patients. The greater efficiency and lower costs to taxpayers of the NHS mean that it has a lower level of hospital beds than other major European countries. To the credit of NHS staff over the past five years, on a like-for-like-basis, a patient’s chance of having to be admitted to hospital as an emergency has fallen by 12% [15]. There have also been substantial reductions in the proportion of people with medium and high dependency who live in care homes [16]. This implies that sicker patients are being successfully looked after without hospitalisation by GPs, community health and social care services, none of whom have seen their expenditure grow at the same rate as acute services.

1.22. Since publication of Next Steps on the Forward View, the NHS over the past two years has

- Rolled out evening and weekend GP appointments nationally, ahead of schedule, so that accessing primary care is easier and more convenient for all patients;

- Enhanced NHS 111, so over 50% of people calling the service now receive a clinical assessment and can be offered immediate advice or referred to the right clinician for a face-to-face consultation;

- Achieved 100% of the population now able to access urgent and emergency care advice through the NHS 111 online service;

- Begun rolling out UTCs across the country, offering a consistent service to patients at 110 locations and introducing the ability to book appointments in UTCs through NHS 111;

- Introduced new standards for ambulance services to ensure that the sickest patients receive the fastest response, and that all patients get the response they need first time and in a clinically appropriate timeframe;

- Introduced comprehensive clinical streaming at the front door of A&E departments, so patients are directed to the service best suited to their needs on arrival;

- Begun implementing Same Day Emergency Care (SDEC), (also known as ambulatory emergency care), increasing the proportion of people who are not admitted overnight in an emergency;

- Reduced the number of people delayed in hospital – reducing the length of stay of patients who remain in hospital for more than 21 days, and freeing up nearly 2,000 beds;

- As a result, in the first half of this year hospitals have used fewer, not more, inpatient bed days for their non-elective patients;

- Continued rapid growth in the number of whole time equivalent A&E consultants, which are up by 30% over the past five years – the fastest growth of any consultant specialty in the NHS;

- Rolled out the Emergency Care Data Set (ECDS) to all major A&E departments to enable better tracking of the quality and timeliness of care.

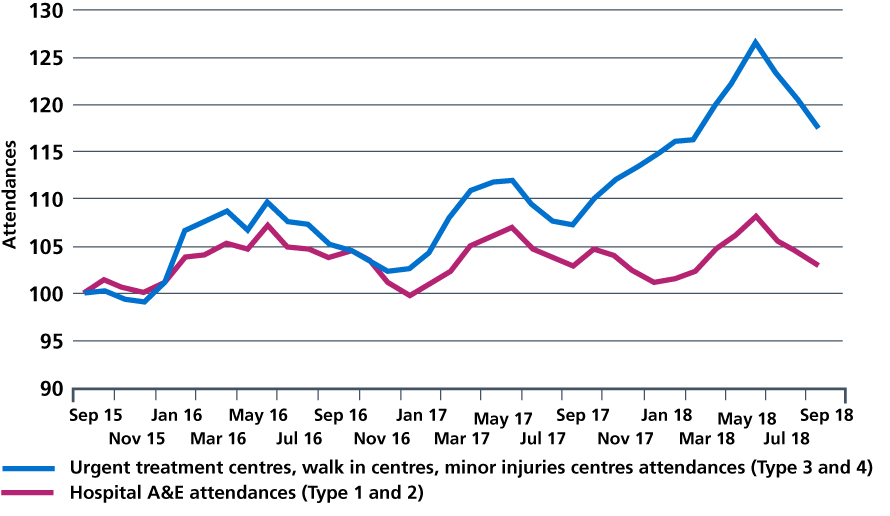

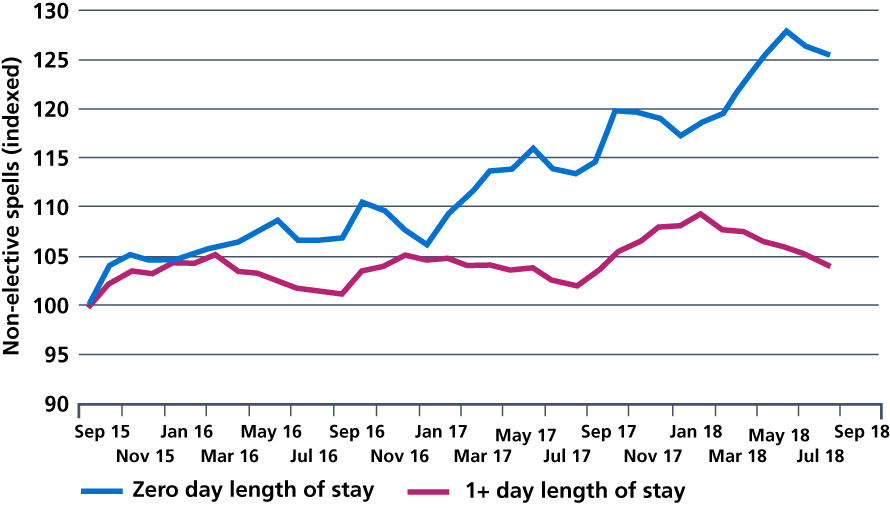

1.23. However we have an emergency care system under real pressure, in the midst of profound change. The number of A&E patients successfully treated within four hours is 100,000 per month higher than five years. New ways of delivering urgent care such as UTCs are growing far faster than hospital A&E attendances, which are up by around 1.5% year-to-date. For those that do need hospital care, emergency admissions requiring an inpatient stay (up by 2.7% year-to-date) are increasingly being replaced by Same Day Emergency Care (up by 10.5%). That, plus good results from action to cut delayed hospital discharges, means inpatient emergency bed days are now actually falling.

1.24. Over the period of this Long Term Plan, by expanding and reforming urgent and emergency care services the practical goal is to ensure patients get the care they need fast, relieve pressure on A&E departments, and better offset winter demand spikes. In looking forward to the next five years, the balance of need for hospital beds will be a product of continuing pressures from an ageing population partially balanced against further gains from changing the model of care, as set out in this chapter. In the ‘base case’ funding, activity and staffing model underpinning this Long Term Plan, we have not built-in as a core assumption potential offsets in hospital beds from increased investment in community health and primary care. Instead we have provided both for the hospital funding and the staffing as if trends over the past three years continue. So to the extent that local areas are able to do better than recent emergency hospitalisation trends – which if the reforms set out in this chapter are implemented effectively should be possible – that will deliver for them an additional local financial, hospital capacity and staffing upside ‘dividend’.

Pre-hospital urgent care

1.25. To support patients to navigate the optimal service ‘channel’, we will embed a single multidisciplinary Clinical Assessment Service (CAS) within integrated NHS 111, ambulance dispatch and GP out of hours services from 2019/20. This will provide specialist advice, treatment and referral from a wide array of healthcare professionals, encompassing both physical and mental health supported by collaboration plans with all secondary care providers. Access to medical records will enable better care. The CAS will also support health professionals working outside hospital settings, staff within care homes, paramedics at the scene of an incident and other community-based clinicians to make the best possible decision about how to support patients closer to home and potentially avoid unnecessary trips to A&E. This includes using the CAS to simplify the process for GPs, ambulance services, community teams and social care to make referrals via a single point of access for an urgent response from community health services using the new model described at paragraph 1.8 above.

1.26. We will fully implement the Urgent Treatment Centre model by autumn 2020 so that all localities have a consistent offer for out-of-hospital urgent care, with the option of appointments booked through a call to NHS 111. UTCs will work alongside other parts of the urgent care network including primary care, community pharmacists, ambulance and other community-based services to provide a locally accessible and convenient alternative to A&E for patients who do not need to attend hospital.

Figure 2: In recent years, acute hospital A&E attendances have been growing at a much slower rate than other urgent care services.

Source: NHS Digital. Secondary Uses Service (SUS) data. 2018.

1.27. Ambulance services are at the heart of the urgent and emergency care system. We will work with commissioners to put in place timely responses so patients can be treated by skilled paramedics at home or in a more appropriate setting outside of hospital. We will implement the recommendations from Lord Carter’s recent report on operational productivity and performance in ambulance trusts, ensuring that ambulance services are able to offer the most clinically and operationally effective response. We will continue to work with ambulance services to eliminate hospital handover delays. We will also increase specialist ambulance capability to respond to terrorism. Capital investment will continue to be targeted at fleet upgrades, and NHS England will set out a new national framework to overcome the fragmentation that ambulance services have experienced in how they are locally commissioned.

Reforms to hospital emergency care − Same Day Emergency Care

1.28. New diagnostic and treatment practices allow patients to spend just hours in hospital rather than being admitted to a ward. This also helps relieve pressure elsewhere in the hospital and frees up beds for patients who need quick admission either for emergency care, or for a planned operation. This is a model co-developed by the Royal College of Physicians and the Society of Acute Medicine, which is being successfully deployed in an increasing number of hospitals. As a result, reported growth in non-elective hospital ‘admissions’ are now disproportionately being driven by so-called ‘zero day admissions’ (patients who are not actually admitted to an inpatient overnight acute bed).

Figure 3: Relative growth in emergency admissions: zero day and 1+ day length of inpatient stay.

Data source: NHS Digital. Secondary Uses Service (SUS) data. 2018.

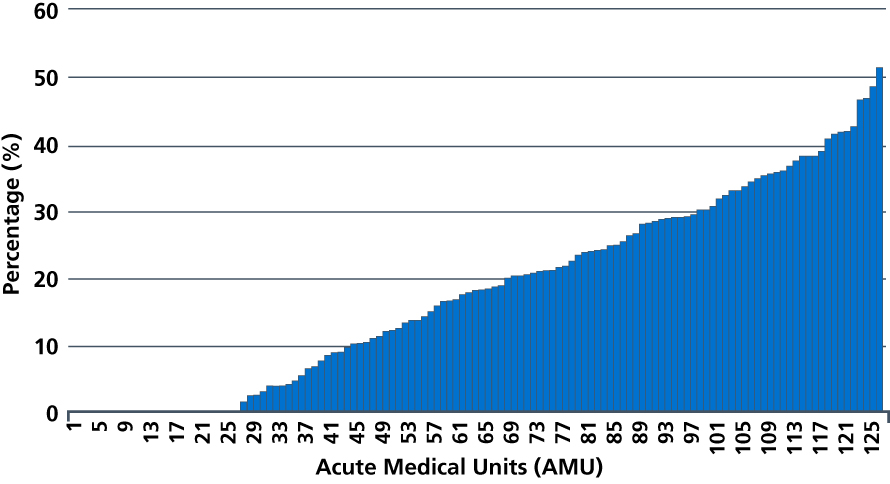

1.29. There are however large differences in the extent to which SDEC has so far been adopted by individual hospitals:

Figure 4: Variation in percentage of initial medical assessments undertaken in ambulatory emergency care.

Source: The Society for Acute Medicine. Society for Acute Medicine Benchmarking Audit. SAMBA18 Interim Report. September 2018.

1.30. Under this Long Term Plan, every acute hospital with a type 1 A&E department will move to a comprehensive model of Same Day Emergency Care. This will increase the proportion of acute admissions discharged on the day of attendance from a fifth to a third. At the same time we should not see the proportion of non-SDEC zero length of stay admissions rise. Hospitals will also reduce avoidable admissions through the establishment of acute frailty services, so that such patients can be assessed, treated and supported by skilled multidisciplinary teams delivering comprehensive geriatric assessments in A&E and acute receiving units. The SDEC model should be embedded in every hospital, in both medical and surgical specialties during 2019/20.

1.31. We will also, as part of the NHS Clinical Standards Review being published in the spring, develop new ways to look after patients with the most serious illness and injury, ensuring that they receive the best possible care in the shortest possible timeframe. For people who arrive in A&E following a stroke, heart attack, major trauma, severe asthma attack or with sepsis, we will further improve patient pathways to ensure timely assessment and treatment that reduces the risk of death and disability. As set out in Chapters Three and Six, we are working with clinical experts and patient groups nationally to ensure that these pathways deliver improvements in patient outcomes, so that the NHS continues to lead the world in the quality of care that it provides for those with the greatest need.

1.32. We will develop a standard model of delivery in smaller acute hospitals who serve rural populations. Smaller hospitals have significant challenges around a number of areas including workforce and many of the national standards and policies were not appropriately tailored to meet their needs. We will work with trusts to develop a new operating model for these sorts of organisations, and how they work more effectively with other parts of the local healthcare system.

1.33. Without access to timely and accurate data we cannot maximise the opportunities to improve care for all patients. The new ECDS is enabling us to better understand the needs of patients accessing A&E departments. We will embed this into UTCs and SDEC services from 2020. We will develop an equivalent ambulance data set that will, for the first time, bring together data from all ambulance services nationally in order to follow and understand patient journeys from the ambulance service into other urgent and emergency healthcare settings.

Cutting delays in patients being able to go home

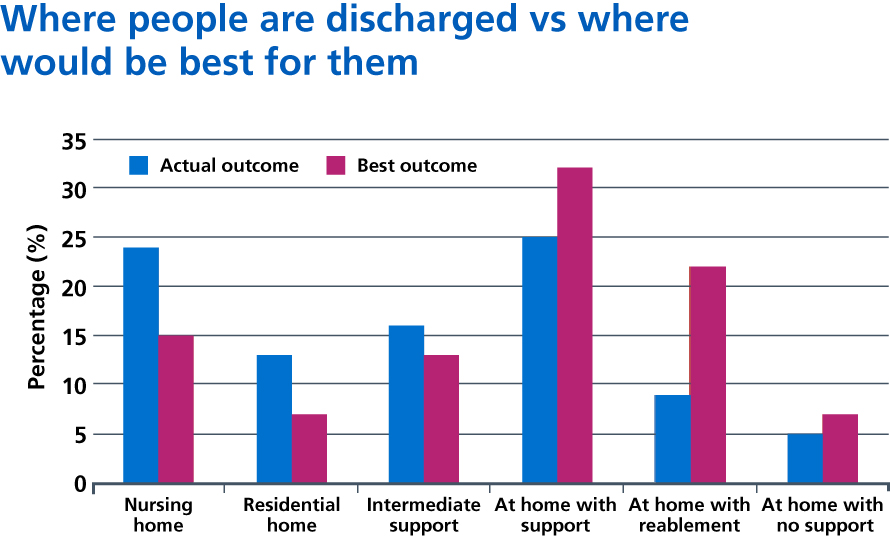

1.34. The NHS and social care will continue to improve performance at getting people home without unnecessary delay when they are ready to leave hospital, reducing risk of harm to patients from physical and cognitive deconditioning complications. The goal over the next two years is to achieve and maintain an average Delayed Transfer of Care (DTOC) figure of 4,000 or fewer delays, and over the next five years to reduce them further. As well as the enhanced primary and community services response set out earlier in this Chapter, we will achieve this through measures such as placing therapy and social work teams at the beginning of the acute hospital pathway, setting an expectation that patients will have an agreed clinical care plan within 14 hours of admission which includes an expected date of discharge, implementation of the SAFER patient flow bundle and multidisciplinary team reviews on all hospital wards every morning.

Source: Newton Europe.

Milestones for urgent and emergency care

- In 2019 England will be covered by a 24/7 Integrated Urgent Care Service, accessible via NHS 111 or online.

- All hospitals with a major A&E department will:

- Provide SDEC services at least 12 hours a day, 7 days a week by the end of 2019/20

- Provide an acute frailty service for at least 70 hours a They will work towards achieving clinical frailty assessment within 30 minutes of arrival;

- Aim to record 100% of patient activity in A&E, UTCs and SDEC via ECDS by March 2020

- Test and begin implementing the new emergency and urgent care standards arising from the Clinical Standards Review, by October 2019

- Further reduce DTOC, in partnership with local authorities.

- By 2023, CAS will typically act as the single point of access for patients, carers and health professionals for integrated urgent care and discharge from hospital care.

References

15. Wyatt, S., Child, K., Hood, A., Cooke, M. & Mohammed, M. (2017) Changes in admission thresholds in English emergency departments. Emerg Med J 34 (12), 773-779. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2016-206213

16. Kingston, A., Wohland, P., Wittenberg, R., Robinson, L., Brayne, C., Matthews, F. & Jagger, C. (2017) Is late life dependency increasing or not? A comparison of the Cognitive Function and Ageing Studies (CFAS). The Lancet. 390 (10103), 1676-1684. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31575-1